The Gender Equality in the Tourism Sector Project is led by the Kaçed Association and implemented with the Association of Turkish Travel Agencies (TÜR- SAB), Italian Association for Responsible Tourism-AITR (Italy), and Gender Studies, o.p.s. (Czech Republic).

The overall objective of our project is to improve entrepreneurship, employment, and employability with a focus on gender equality. Six specific objectives have been set to achieve this overall goal:

Development of digital tourism applications for tourism enterprises

Revealing the tourism resource value of Kaçkar Mountains National Park and Fırtına Valley

Establishment of a tourism communication mechanism between Italian, Czech, and Turkish tourism interest groups

Increasing the digital tourism skills of tourism sector employees

Kaçkar Mountains National Park and Fırtına Valley (Türkiye)

Gran Paradiso National Park (Italy)

Šumava National Park (Czech Republic)

(1) 200 tourism enterprises located in Kaçkar Mountains National Park and Fırtına Valley Basin (Türkiye), Gran Paradiso National Park (Italy), and Šumava National Park (Czech Republic)

(2) 400 young individuals working in the tourism sector in Kaçkar Mountains National Park and Fırtına Valley Basin,

(3) 400 unemployed women and young individuals living in rural settlements of Kaçkar Mountains National Park and Fırtına Valley Basin

(4) 200+ young individuals with visual and hearing impairments

(5) 500 Local residents

The families of our project target group, social and business circles, and media representatives constitute the final beneficiaries of our project.

Activity 1: Establishment of the Project Office and Team

Activity 2: Preparation and publication of FreemiumTOURISM Application

Activity 3: Digitalization of Kaçkar Mountains National Park

Activity 4: Activities to Increase the Visibility of Kaçkar Mountains National Park and Fırtına Valley:

Activity 4.1: Documentary Film

Activity 4.2: Preparation and Reproduction of Information Booklets

Activity 5: Preparation and publication of Audio and Video KAÇKAR Application

Activity 6: Digital Tourism Workshop Activity

Activity 7: Activities for Sharing Experience in Project Co-Applicant Countries:

Activity 7.1: The Italian Case for Responsible and Digital Tourism

Activity 7.2: The Czech Example for Gender and Tourism

Activity 7.3: Stakeholder Meeting and Photo-SAFARI in Türkiye

Activity 8: Ecological Tourism Potential Activities:

Activity 8.1: Conducting Field Research

Activity 8.2: Organizing an Ecological Tourism Potential Workshop:

Activity 9: Increasing the Role of Women and Youth in Tourism Activities:

Activity 9.1: Field Research on Women's Labor in Tourism

Activity 9.2: Establishment of KACED Social Incubation Center:

Activity 9.3: Creation and publication of the Tourism and Gender Portal:

Activity 10: Accessibility Activities for the Project

Activity 11: Awareness and Promotion:

Activity 12: Preparation of the Future Planning of the Project

1) An effective project management and coordination unit will be established after the signing of the project contract. An effective and robust monitoring, measurement, evaluation and reporting methodology will be developed during the project period

2)FreemiumTURIZM Application will be prepared and published on Android and iOS.

3) Digital maps of Kackar Mountains National Park will be produced and reproduced in a booklet.

4)A documentary film will be prepared to increase the visibility of Kaçkar Mountains National Park and Fırtına Valley;

Information booklets on Kaçkar Mountains National Park and Fırtına Valley will be prepared and reproduced.

5) Audio and Video KACKAR Application will be prepared and published on Android and iOS.

6) Digital Tourism Workshop will be held.

7) Activities for sharing experience in the Project Co-Applicant countries (Italy Case study for Responsible and Digital Tourism, Czech Republic case study for Gender and Tourism and Stakeholder meeting and photo-Safari study in Türkiye) will be carried out.

8) Within the scope of ecological tourism potential activities, one field survey will be conducted; Ecological Tourism Potential Workshop will be organized.

9) In order to increase the role of women and young individuals in tourism, a field research on "Women's Labor in Tourism" will be carried out; a Kaced Social Incubation Center will be established; a portal on "Tourism and Gender" will be created and published.

10) All materials to be produced within the scope of the project will be translated into audio-visual materials and made available to disabled individuals.

11) Awareness and promotional activities will be developed for the visibility of the project.

12) For the sustainability of the project, a future plan meeting will be held with the co-applicants.

For detailed information about the project, please contact with our project coordinator Dr. Yasar YEGEN. E-mail: yasar@kaced.org Telefon: 0542 805 16 53

For detailed information about the project, please contact with our project coordinator Dr. Yasar YEGEN. E-mail: yasar@kaced.org Telefon: 0542 805 16 53

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| e-mail: info@kaced.org Address: Çarşı Mah., Hacı Eşref Cad., Boştan Işhanı, No:16/, 302, 53100 Merkez/Rize, Türkiye Tel: 0 464 715 14 16 Web: www.kaced.org | e-mail: info@tursab.org.tr Address: Dikilitaş Mah. Aşık Kerem Sok. No:40 Fulya 34349 Beşiktaş/Istanbul, Türkiye tel: +90212 259 84 04 web: www.tursab.org.tr | e-mail: info@genderstudies.cz Address: Masarykovo nábřeží 8, Prag 2, Czech Republic Tel: +420 224 915 666 web: www.genderstudies.cz | e-mail:info@aitr.org Address: Via Cufra, 29, 20159 Milano, Italy Tel: +02-25785763 web: www.aitr.org |

Gender inequality has remained a global social issue occupying the international agenda for years, with minimal progress achieved worldwide. It has also been included among the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set during the United Nations Sustainable Development Summit in 2015. In this respect, international organizations have suggested that the tourism sector, which employs a high number of women due to horizontal stratification, should be promoted as a tool to strengthen women's positions. A robust body of literature highlights the significant role tourism plays in empowering women. These studies predominantly focus on the working conditions of women employed in specific tourism regions or fields, thus remaining at a micro level. However, the broader macroeconomic spillover effects of female employment in this sector are often overlooked in the general literature. Through induced effects, the tourism sector can expand male employment at the expense of female employment on a national scale. The sector's forward and backward linkages to male-dominated fields such as construction, technical services, and transportation can restrict the national spillover effect of female employment generated within tourism. Consequently, while the tourism sector is recommended as a means of promoting women's empowerment, it may lead to unequal development in national female employment, potentially resulting in outcomes contrary to policy objectives.

The tourism sector, with its high domestic value added, is one of the sectors that generates the highest foreign exchange earnings compared to other export-oriented sectors. While tourism has a high share in the service sector, it also indirectly affects other sectors through backward linkages. As in other service sectors, labor demand is continuous as production is carried out with labor-intensive techniques. In addition, as a result of the “feminization” of the service sector, or the horizontal stratification of relational work carried out mostly by women, the tourism sector has been the focus of policies aimed at women's empowerment as a sector where women are predominantly employed. Especially the fact that accommodation and food and beverage production are considered women's work in patriarchal societies has made tourism a sector where women constitute the majority.

Gender-based discrimination is among the most significant reasons for the challenges women face in working life, including access to employment opportunities, wages, working conditions, and social security. It also constitutes a barrier to sustainable development. Prejudices and obstacles caused by gender lead to inequalities between men and women in tourism, a sector critical for national economies and development, as in all sectors. While sex refers to the biological distinction between men and women, gender refers to the socially constructed and culturally sourced differences between men and women, highlighting the unequal social division between “masculinity” and “femininity” (Marshall, 1998). The roles, behaviors, and attributes constructed by society for men and women are expressed through the concept of gender (UNDP, 2019). Gender often has negative implications for women in the labor market. Gender segregation in employment refers to unequal participation rates and occupational structures between men and women. Occupational gender segregation occurs in two ways: vertical segregation, where men cluster at the top of professional hierarchies and women at the bottom, and horizontal segregation, where men and women perform different tasks at the same occupational level, with women assigned lower responsibilities (Marshall, 1998). Unemployment and the lack of decent work remain major global issues, with women particularly disadvantaged in labor force participation rates. Globally, 78% of men (aged 15–64) are in the labor market, compared to 55% of women (WEF, 2019). This disparity is a significant factor in preventing women’s economic independence and deepening gender inequality. The World Bank research reveals striking results regarding the impact of this inequality on the global economy. The results reveal that while women’s participation in the workforce accounts for 37% of the global gross domestic product (GDP), eliminating gender-based discrimination and achieving equal participation by women and men in the workforce could increase the global GDP by an additional 26% by 2025 (World Bank, 2017). When assessing Türkiye's position on gender equality, it is evident that the country lags far behind the average of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) member states. Due to factors such as low participation of women in employment, politics, and decision-making mechanisms, Türkiye ranks 130th out of 144 countries in the "Global Gender Gap Index" (Special Commission Report on the Role of Women in Development, 2018). Women’s employment and labor force participation in Türkiye are significantly lower than men’s. According to data from the Turkish Statistical Institute (TurkStat) as of December 2019, the labor force participation rate in Türkiye is 72% for men and 34.4% for women. The inequality against women extends beyond access to employment opportunities to include wage conditions. A report titled Measurement of Gender-Based Wage Gap: Türkiye Implementation, prepared in collaboration with the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the Turkish Statistical Institute, highlights this disparity. Based on 2018 data, the wage gap between men and women favors men by 21.1%. The report also addresses the wage gap between mothers and fathers, noting a difference of 19% (Ministry of Family, Labor, and Social Services, 2020). The unfavorable quantitative representation of women in employment reflects a similar qualitative picture. According to the Household Labor Force Survey conducted by the Turkish Statistical Institute, the proportion of male managers in Türkiye was 82.7% in 2017, compared to 17.3% for female managers (IKV, 2019). Similarly, 2019 ILO data indicate that women’s share in employment in Türkiye is 25%, their share in total management is 13%, their representation in top executive positions in enterprises is below 10%, and their share in middle and senior management is under 12% (Akgül, 2020). Tourism, as a labor-intensive sector within the service industry, has significant economic impacts. Although women’s employment in various sectors is lower than men’s, the number of women employed in tourism is higher. Globally, approximately 61 million women are employed in the tourism sector (UNWTO, 2019). Tourism provides new employment opportunities for women and plays a crucial role in their active participation in the workforce. Based on 2019 data, while women’s employment globally across all sectors is 44.6%, it is 54% in the tourism sector (Yetiş and Çalışkan, 2020). However, Türkiye is among the countries in Europe with the lowest proportion of women employees in tourism; women’s employment in accommodation and food and beverage services is 14.83% (Akgül, 2020). Although women make up the majority of the tourism sector workforce, they tend to occupy the lowest-paid and lowest-status positions (UNWTO, 2019). Gender-based division of labor plays a significant role in shaping women’s positions in tourism. Women are often employed in lower-level roles in departments like housekeeping, kitchens, and service areas, which are perceived as extensions of domestic work. The 2019 Global Report on Women in Tourism by the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) highlights women’s distance from decision-making positions in the sector. While 70% of employees in the accommodation sector are women, they account for only 40% of managerial roles, 20% of general management positions, and less than 8% of senior executive roles (Akgül, 2020). The UNWTO report also provides data on the gender pay gap in the tourism sector, revealing that women earn approximately 15% less than men in similar roles. Beyond low wages, women also frequently work as unpaid family laborers in family-owned businesses (UNWTO, 2019). Gender inequality partially limits women’s access to benefits such as health insurance and pensions, which are tied to formal employment. Due to societal expectations, women often choose jobs with flexible working hours or part-time positions to care for family members, or they move into informal employment. Since social security systems require formal employment and regular premium payments, women not only face low wages but also lose access to employment-related benefits such as social security. Additionally, the tourism sector is characterized by long and demanding working hours, seasonal employment relationships, a lower demand for educated and skilled labor compared to other sectors, and low rates of unionization and collective bargaining. These factors also influence the roles and positions of women employed in the tourism sector (Yetişkin and Çalışkan, 2020). Gender inequality is a significant barrier to women’s efforts to achieve economic independence. Research conducted with the participation of tourism business managers in Ankara to determine the impact of the roles and responsibilities determined for women and men on women's employment highlights that while the primary motivation for women to work is economic independence, the main reason for leaving their jobs is the conflict between work and family responsibilities (Ikiz, 2020). This research is particularly noteworthy for demonstrating how gender impacts the position of women employed in the sector. Participants indicated that although women are believed to influence organizational productivity positively, jobs in the tourism sector are divided by gender. Women are hired for jobs deemed suitable for their gender, while men are employed in more demanding roles requiring flexibility. The study also found that managers rationalize this gender-based division by citing reasons such as specific job requirements (Ikiz, 2020). In another research conducted with women employees in tourism businesses in Şanlıurfa, more than half of the participants stated that there is a division of jobs as "women’s work" and "men’s work" in the sector. Additionally, approximately 60% of the participants expressed the opinion that there is a wage gap between men and women (Çakır et al., 2017). In connection with women’s employment, women remain in secondary positions when it comes to establishing their own businesses. Research involving 40 women entrepreneurs in prominent tourism regions, including Alanya, Kaş, Bodrum, and Marmaris, examined the effects of gender inequality on women’s entrepreneurship. The participants emphasized the barriers women face in starting their businesses. The study highlighted that from the perspective of men being seen as responsible for providing for the family, women’s contributions to the family economy are undervalued. It also pointed out that women’s work and entrepreneurship are not widely accepted (Altındal, 2016).

Through the employment opportunities it creates for women, the tourism sector has a positive impact on gender inequality through material improvements at the relational and macro levels of the gender structure. Compared to other sectors, the hiring requirements in the tourism sector are relatively low; therefore, women, whose work experience and qualifications lag behind men, are more likely to be employed in this sector. Hence, on a relational level, women who have the opportunity to work in the tourism sector not only increase their representation rates and reduce their performance concerns but also facilitate their access to social solidarity networks that can combat cultural stereotypes about them. They also increase their gender awareness and consciousness in the cultural dimension by increasing their income at the macro level and having the opportunity to improve their skills. Despite these advantages over women's labor, the tourism sector might also lead to an increase in the gender gap by immobilizing women in relatively low job positions. In this respect, studies examining the gender structure in the tourism sector at the macro level mainly focus on the discussion of strengthening women's position in society through tourism employment. The concept of empowerment from a gender perspective includes the social, economic, and political transformation of women's control over their lives and how they are empowered to act together to bring about these transformations. In this context, women's employment in paid work can be considered a necessary requirement for their economic empowerment. However, studies show that women's employment has contradictory economic consequences. While macro-level studies reveal that women work in more exploitative production structures (export-oriented sectors) and informal sectors, micro-level studies suggest that women are empowered in everyday life (Him, 2020). The same dilemma can be found in the literature on the empowerment of women employed in the tourism sector. Many studies on tourism reveal that women are predominantly employed in relatively low-paid positions such as cleaning, accommodation, and reception, and that the division of jobs in the sector is structured accordingly (Sinclair, 1997). On the other hand, country- or narrow region-based empirical and qualitative studies, which cover the majority of the tourism and gender literature, reveal that women are empowered in many ways through tourism employment. First, tourism employment enables women to be financially independent from men in the family. Many studies have shown that new job opportunities in the tourism sector, which lead to financial independence, also offer women more comfortable working conditions compared to their traditional workloads, support their entrepreneurial activities, strengthen their ability to take control of their income, and raise their qualifications through job training. Micro-based studies have shown that women's economic empowerment provides them with the self-confidence and organizational opportunities to transform and fight against the conditions imposed by the patriarchal social structure in which they live.

Another perception that hinders women's employment in tourism is the prejudice against women working outside the home. A study on women's employment in tourism in the Cappadocia region reveals that it is not considered appropriate for women to work in the tourism sector, that tourism is a job for men, and that it is more appropriate for women to stay at home. It is argued that some of the social barriers to women's employment in Türkiye are the interaction of the concept of gender with culture. Examples of these include harassment, gossip, and honor. It is claimed that employers and women's husbands do not look favorably on women's employment due to such perceptions. It is believed that the perception of the interaction between men and women as an unpleasant situation due to the inculcation of gender differences at an early age is among the unbreakable taboos of women's employment today. It is argued that families' preference for avoiding interactions with male individuals outside the family, coupled with political authorities expressing views that support this stance, reinforces the negative perception in society regarding men and women being together for any purpose. Although the tourism sector poses numerous challenges for women, it is considered to be a great opportunity for achieving gender equality. It is believed that as the number of women employed in the sector increases, the perception of “working women” in their families and circles will change over time. It is stated that it is not only important for the family and the social environment but also for tourism authorities to realize that a tourism sector without women cannot survive.

According to TurkStat 2018-2024 data, although women's participation in business life in managerial positions has increased, this rate is not considered sufficient. It cannot be said that women have progressed at the same rate as men. As reported by Anadolu Agency, the proportion of women in managerial positions in Türkiye was 14.4% in 2012, which increased to 16.3% in 2018. Although this represents a 1.9% increase, it is evident that the growth over the years has remained quite modest. Among the reasons cited for the lack of women in managerial positions are behavioral issues in the workplace and discouraging attitudes that undermine women's confidence and enthusiasm. Even in sectors where women are highly represented, the predominance of male managers stands out as a notable issue. Despite women attaining a good level of education today, the number of women in managerial positions is reported to be below expectations. One reason for this is the lack of equal opportunities during recruitment processes. Since men and women are often hired at different levels, women tend to lag behind men in terms of career advancement due to their initial status. Another perspective attributes this issue to discriminatory policies, such as vertical and horizontal discrimination. For example, horizontal discrimination can be seen when male employees in the same position as female employees take on more responsibilities. It is worth noting that these responsibilities are often taken strategically to facilitate promotions. Vertical discrimination, on the other hand, refers to women being assigned lower-status roles with fewer responsibilities, which keeps them in the background. As a result, men are more likely than women to occupy managerial positions. Fundamentally, due to women’s nurturing roles and their responsibilities toward their homes and children, they are unable to dedicate sufficient time to their jobs. This often forces women to work harder than men to earn promotions or climb the career ladder, leading to slower or even no progress in some cases. Additionally, it is believed that compared to men, women seeking promotions or managerial positions are sometimes compelled to sacrifice time with their families or even separate from them. Challenges faced by women in professional life include representation issues, mobbing (psychological harassment or attrition policies), the glass ceiling, and the queen bee syndrome. In the tourism sector—known as the smokeless industry of the service sector—women constitute the majority of the workforce. This is mainly attributed to the perception that many jobs in the tourism sector are more "feminine." Jobs such as cooking, cleaning, welcoming guests, and preparing meals are considered inherently female roles, leading to a higher concentration of women in the tourism workforce. However, it is evident that these roles are predominantly categorized as low-level jobs. Even in the tourism sector, it can be observed that women are employed in roles that do not allow them to rise to key positions (e.g., managerial roles). This situation is described as an invisible system that hinders women’s career advancement, regardless of their achievements or merit. The presence of the glass ceiling syndrome is well-documented not only in the tourism sector but across many industries. The concept of mobbing is essentially a phenomenon based on psychological violence. As in other sectors, the tourism industry also experiences mobbing. Reasons for mobbing against women include male managers preventing women’s promotions, men’s preference for male managers due to a patriarchal mindset, and the perception of workplaces as part of men’s social environments. Men can cope with workplace stress more easily as they socialize more than women. Women, however, often return to their homes and children—considered their responsibility—after work, which places them in a continuous cycle of work and home, making it harder for them to withstand psychological pressures. Another reason for hesitation in appointing women to managerial roles is related to pregnancy, maternity duties, and the possibility of women taking time off work. These factors are seen as obstacles to appointing women to leadership positions. Queen Bee Syndrome is another issue, defined as women in high positions aligning more closely with men, distancing themselves from other women, and making things difficult for female colleagues. This behavior involves adopting a male-oriented mindset and altering their position accordingly. As in other sectors, such syndromes are also observed in the tourism industry.

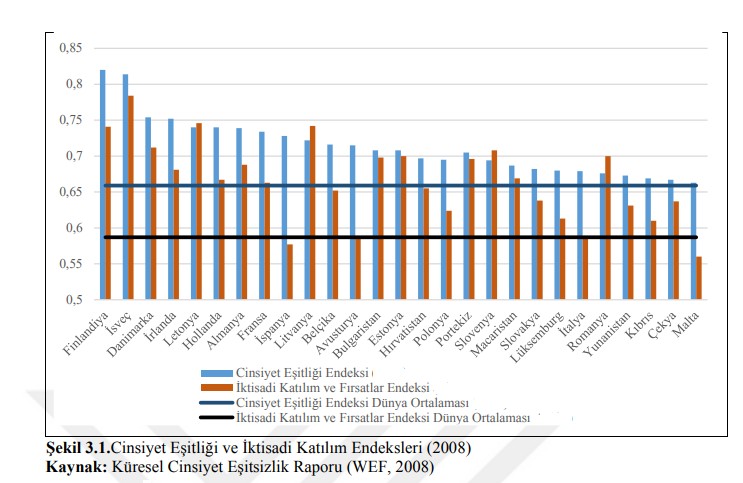

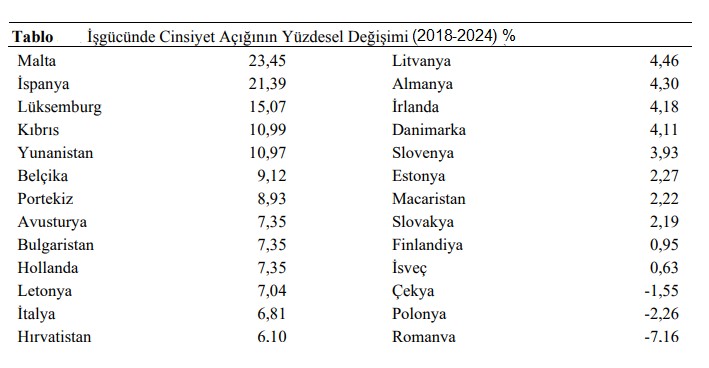

This section provides a descriptive analysis of the extent of gender inequality in the labor market in EU countries using the Gender Equality Index derived from the Global Gender Gap Report published by the World Economic Forum for EU countries. The report examines gender inequality across four dimensions: (1) economic participation and opportunities, (2) educational attainment, (3) health and survival, and (4) political empowerment. Economic Participation and Opportunities Index: This sub-index illustrates the level of women’s participation in economic activities and the extent of equality in opportunities based on three key concepts: labor force gap, wage gap, and advancement gap. The labor force gap is measured as the difference in labor force participation rates between men and women. The wage gap is calculated using the ratio of estimated earned income for men and women, combined with data from the World Economic Forum’s Executive Opinion Survey regarding pay for equal work. The advancement gap is measured by the proportion of women among parliament members, senior officials, and managers, as well as their share among technical and professional workers (WEF, 2023). ● Educational Attainment: This sub-index measures the disparity in access to primary, secondary, and tertiary education between women and men. ● Health and Survival: This sub-index evaluates gender differences in health conditions, using indicators such as the sex ratio at birth—accounting for the termination of pregnancies due to male-child preference—and differences in life expectancy. ● Political Empowerment: This sub-index measures the gap between women and men in top political decision-making positions. It considers the ratio of women to men in ministerial positions and parliamentary seats and incorporates the proportion of years served by women as head of state or government compared to men over a 50-year period (WEF, 2024). Since this study focuses on the economic empowerment of women in the tourism sector, the emphasis will be on the Economic Participation and Opportunities sub-index. This section evaluates EU countries by considering both the global gender equality index and the Economic Participation and Opportunities sub-index, along with its related variables.

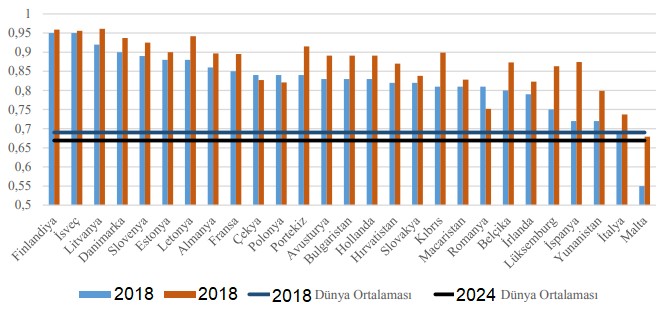

EU countries' gender equality and economic participation indices in 2024 are shown in the Figure below. The chart reveals that in 2024, the gender inequality index of EU countries was generally above the world average. Only Cyprus (0.669), the Czech Republic (0.667), and Malta (0.663) had ratios almost equal to the world average (0.659). These countries are among the countries that joined the European Union in 2004 and afterward, which explains this deviation. As of 2008, significant differences emerged between the older and the newer member states of the Union. As regards the economic participation and opportunities index, countries other than Austria (0.587), Italy (0.587), Malta (0.663), and Spain (0.577) were above the world average (0.587). By 2024, except for Lithuania and Latvia, the economic participation and opportunities index was higher than the gender equality index in EU countries. This shows that EU member states are further advanced in other dimensions of gender equality, namely gender equality in health and education, than in economic equality.

Figure: Gender Equality and Economic Participation Index 2024

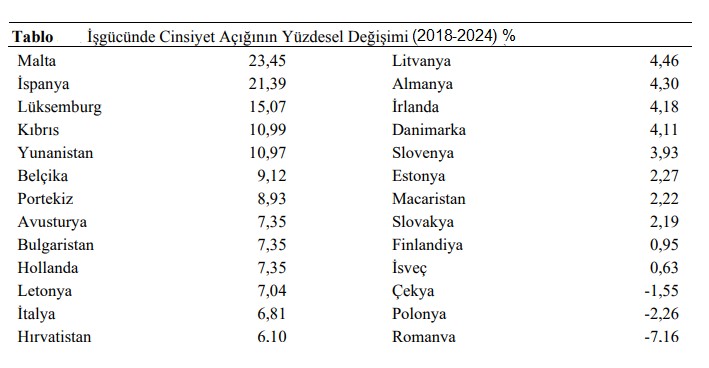

The gender gap in the labor force is simply the quotient of the labor force participation rates of women and men. This is the most important indicator in gender studies as it is an output of the factors that prevent women from entering the labor market. A value close to 1 indicates that women are able to supply as much labor as men and that there are few barriers to this. As shown in the figure, Sweden (0.95-0.96) and Finland (0.95-0.96) had the lowest gender gap in the labor force in both years. The countries with the lowest realizations of this indicator in both years were Malta (0.55-0.68) and Italy (0.69-0.74), which were below the world average in 2008 (0.69) and above it in 2024 (0.67). According to the table below, which shows the change in the gender gap in the labor force between 2018 and 2024, Malta has closed the gender gap in the labor force at the highest rate. In the Czech Republic, Poland, and Romania, the gap widened in 2024 compared to 2018. The pattern emerging in the economic participation and opportunities index is more clearly seen here. Four of the top five countries that have closed the gender gap in the labor force the fastest are Malta, Spain, Cyprus, and Greece, which are considered global tourism hubs. In this framework, it can be concluded that employment opportunities created in the tourism sector, where women predominantly work due to horizontal stratification, positively affect women's labor force participation.

Figure: Gender gap in the labor force

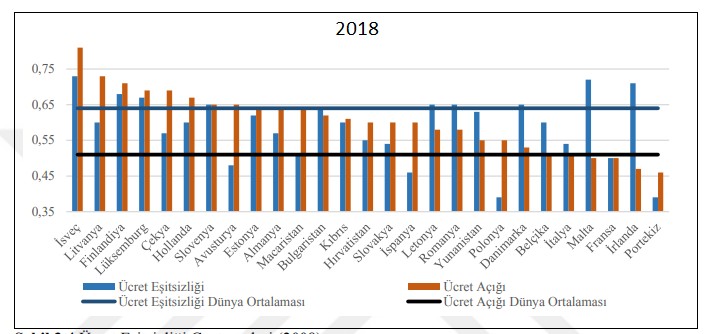

The Global Gender Gap Report published by the World Economic Forum measures wage equality in two ways. First, it calculates the ratio of average income earned by men and women. Second, it uses data from the Executive Opinion Survey to assess pay for equal work between men and women. These are referred to as wage gap and wage equality, respectively. Wage disparities reflect the position of women in the labor force compared to men and represent the outcomes of profound social and economic factors and developments, which significantly impact the welfare levels of both genders. Unequal wage progression between men and women results in a compounded effect that reduces women’s chances of earning high incomes over their lifetimes. Women are less likely to be promoted due to vertical stratification, limiting their access to higher earnings and forcing them to invest less in post-retirement savings. Additionally, women’s career advancement is restricted as they are often excluded from work processes or unable to dedicate substantial effort to work due to household responsibilities. According to the data, there is an inconsistent relationship between wage inequality data collected from the Executive Opinion Survey and wage gap data calculated from the average income ratio of men and women. For countries such as Malta, Ireland, Greece, Belgium, and Denmark, wage inequality data are significantly higher than the wage gap. The first set of data indicates that men and women receive equal pay for equal work, while the latter suggests that women earn substantially less than men on a national level. This discrepancy shows that, despite the implementation of equal pay for equal work policies, women on average earn much less than men in most EU countries—likely due to vertical stratification. Therefore, using wage gap data offers a more realistic picture. When compared to the global average for 2018, EU countries, except for a few countries, performed below the world average. As regards the wage gap, Belgium, Italy, Malta, Malta, France, Ireland, and Portugal performed below the world average, while all other member countries were above average. No discernible pattern was found between older EU member states, including founding countries, and newer members that joined after 2014. Unlike patterns identified in global tourism hotspots, no such trend emerged for wage inequality indicators in 2018.

Figure: Wage Inequality Indicators (2018)

For 2024, the results again show no discernible pattern between wage inequality and wage gap indicators. Finland, Belgium, Ireland, Luxembourg, Estonia, and Malta displayed significantly higher inequality data than wage gap data, while in Croatia, France, Portugal, Spain, and Bulgaria, the gap data were substantially higher. This suggests that inequality data, based on survey findings, fail to account for the impact of vertical stratification on wages. In 2024, founding or older EU member states and newer members ranked similarly. Slovenia demonstrated the highest performance, while Malta and Austria had the lowest.

Figure: Wage Inequality Indicators (2024)

The aim of the field research on “Women's Labor in Tourism” is “to examine the challenges faced by women working or wishing to work in the tourism sector in the Kaçkar Mountains National Park and Fırtına Valley Basin and to propose solutions, and to determine the status of tourism-oriented women's entrepreneurship in the Kaçkar Mountains National Park and Fırtına Valley Basin.”

The research was conducted in 33 rural settlements within the Kaçkar Mountains National Park and Fırtına Valley Basin. Rural Settlements Covered in the Study: 1. Ayder Plateau 2. Huser Plateau 3. Kaçkar Plateau 4. Kaleköy Plateau 5. Karap Plateau 6. Karmik Plateau 7. Karunç Plateau 8. Kavrun Plateau (Lower and Upper Kavrun Plateaus) 9. Gito Plateau 10. Koçdüzü Plateau 11. Komati Plateau 12. Komati Plateau 13. Lakubar Plateau 14. Lordeçur Plateau 15. Nafkar Plateau 16. Ovit Plateau 17. Palakçur Plateau 18. Palovit Plateau 19. Pokut Plateau 20. Sal Plateau 21. Samistal Plateau 22. Topluca Plateau 23. Trovit Plateau 24. Verçenik Plateau 25. Dikkaya Village 26. Kale Village 27. Meydan Village 28. Ortaklar Village 29. Ortayayla Village 30. Şenköy, Çamlıhemşin 31. Şenyuva Village 32. Yukarışimşirli Village 33. Zilkale Village

In the first step, a comprehensive literature review was conducted within the framework of the research objectives to prepare for the survey studies. Fundamental statistical data on ecological tourism were obtained. In the second step, a questionnaire form consisting of 26 questions was developed in collaboration with the experts of Limitsizsiniz Danışmanlık [Consultancy] and the project team. The field research was conducted in June 2024 in 33 rural areas in Kaçkar Mountains National Park and Fırtına Valley, with face-to-face interviews with 1200 people. Interviews were conducted by experts from Limitsizsiniz Danışmanlık [Consultancy] and representatives of Kaçed Association. A total of 1200 participants answered the questionnaire. In the third step, the data obtained in the field were analyzed. The questionnaire responses collected in the research were analyzed using the SPSS for Windows 19.0 program after data editing by the experts of Limitsizsiniz Danışmanlık [Consultancy]. Analyses included graphical representations of percentage distributions, cross-evaluations of demographic features, and multidimensional scaling analyses of categorical questions and demographic data.

After the field research on "Women's Labor in Tourism" was conducted, a comprehensive and detailed research report was prepared and printed in 50 copies. Field Research Report Booklet:

Ecological Tourism Potential Field Research The primary aim of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness of the existing ecotourism potential in Kaçkar Mountains National Park and Fırtına Valley, assess local people's perspectives on tourists, identify challenges related to ecotourism, and explore alternative ways for locals to engage in ecotourism activities. The importance of ecotourism in preserving the region’s natural beauty underscores the necessity of implementing sustainable tourism principles. Education and income levels are known to influence interest in ecotourism. Thus, this study aims to establish policies promoting sustainable tourism that include the local population and assess the feasibility of these policies. Another aim of this research is to examine the effectiveness of education and awareness-raising campaigns to protect natural areas and balance tourism. Participation in ecotourism activities tends to be higher among individuals with higher education and income levels. Therefore, the study aims to identify supportive measures, such as education programs, guidance, awareness activities, and incentives for entrepreneurs. This approach will enable the proposal of policies and practices that support environmental conservation efforts. The ultimate goal of the research is to promote greater participation of local communities in environmental sustainability programs. Residents should be supported in sustainable tourism efforts, as cultural experiences are as essential as preserving natural areas. By focusing on tourist preferences and business efficiency, the region's tourism potential can be increased, and environmental protection goals can be supported. Therefore, the study aims to contribute to developing sustainable tourism in the Kaçkar Mountains and Fırtına Valley in line with these objectives.

Research Location The research was conducted in 33 rural settlements within the Kaçkar Mountains National Park and Fırtına Valley Basin. Rural Settlements Covered in the Study: 1. Ayder Plateau 2. Huser Plateau 3. Kaçkar Plateau 4. Kaleköy Plateau 5. Karap Plateau 6. Karmik Plateau 7. Karunç Plateau 8. Kavrun Plateau (Lower and Upper Kavrun Plateaus) 9. Gito Plateau 10. Koçdüzü Plateau 11. Komati Plateau 12. Komati Plateau 13. Lakubar Plateau 14. Lordeçur Plateau 15. Nafkar Plateau 16. Ovit Plateau 17. Palakçur Plateau 18. Palovit Plateau 19. Pokut Plateau 20. Sal Plateau 21. Samistal Plateau 22. Topluca Plateau 23. Trovit Plateau 24. Verçenik Plateau 25. Dikkaya Village 26. Kale Village 27. Meydan Village 28. Ortaklar Village 29. Ortayayla Village 30. Şenköy, Çamlıhemşin 31. Şenyuva Village 32. Yukarışimşirli Village 33. Zilkale Village

Research Methodology A questionnaire was conducted in 33 rural areas identified as critical in the Kaçkar Mountains National Park and Fırtına Valley. It aimed to measure the effectiveness of the existing ecotourism potential and to investigate the local population's views on tourists, the challenges they face in ecotourism, their expectations, and the alternative participation opportunities for locals to enhance ecotourism effectiveness. The research data are intended to inform the workshop “Ecotourism Potential of Kaçkar Mountains National Park and Fırtına Valley.” Additionally, the findings are expected to provide a comprehensive regional analysis of relevant institutions and organizations. In the first step, a comprehensive literature review was conducted within the framework of the research objectives to prepare for the survey studies. Fundamental statistical data on ecological tourism were obtained. In the second step, a questionnaire form consisting of 26 questions was developed in collaboration with the experts of Limitsizsiniz Danışmanlık [Consultancy] and the project team. The field research was conducted in June 2024 in 33 rural areas in Kaçkar Mountains National Park and Fırtına Valley, with face-to-face interviews with 1200 people. Interviews were conducted by experts from Limitsizsiniz Danışmanlık [Consultancy] and representatives of Kaçed Association. A total of 1200 participants answered the questionnaire. In the third step, the data obtained in the field were analyzed. The questionnaire responses collected in the research were analyzed using the SPSS for Windows 19.0 program after data editing by the experts of Limitsizsiniz Danışmanlık [Consultancy]. Analyses included graphical representations of percentage distributions, cross-evaluations of demographic features, and multidimensional scaling analyses of categorical questions and demographic data. After the field research on "Women's Labor in Tourism" was conducted, a comprehensive and detailed research report was prepared and printed in 50 copies. Field research report:

A three-day workshop was held with the participation of 30 tourism interest groups operating in the Kackar Mountains National Park and the Firtina Valley. All of the workshop participants were women. The workshop was attended by 14 representatives from tourism businesses operating in the Kackar Mountains National Park and the Firtina Valley, 1 representative from the Rize Culture and Tourism Association, 1 representative from the Markarize Culture and Art Association, 1 representative from the Rize-Artvin Tourism Association, 1 representative from the Black Sea Tourism Operators Association, 1 representative from the Rize Directorate of Culture and Tourism, 1 representative from the Kackar Mountains National Park Directorate, and 10 individuals living in rural settlements (villages, hamlets, and highlands) within the borders of the Kackar Mountains National Park.

Workshop photos:

In the workshop titled "Ecological Tourism Potential," the "Ayder Ecotourism Action Plan" was developed in collaboration with all stakeholders. The Ayder Ecotourism Action Plan was printed in 50 copies each in Turkish and English. Ayder Ecotourism Action Plan Booklet:

Unemployed women and young people, as well as women and young people with visual and hearing impairments living in rural settlements in the Kackar Mountains National Park and Firtina Valley Basin, were provided with training on ecotourism practices, and mentoring support was offered. In the incubation center, training was also provided to young people currently working in the tourism sector to enhance their professional skills, and mentoring support was offered. More than 100 people have benefited from the incubation center.

Unemployed women and young people, as well as women and young people with visual and hearing impairments living in rural settlements in the Kackar Mountains National Park and Firtina Valley Basin, were provided with training on ecotourism practices, and mentoring support was offered. In the incubation center, training was also provided to young people currently working in the tourism sector to enhance their professional skills, and mentoring support was offered. More than 100 people have benefited from the incubation center.

Six information booklets have been prepared and published within the scope of the project:

Indices developed to concretely demonstrate gender-based inequalities confirm that women are not equal to men and are discriminated against in many countries around the world. According to statistics and reports published by the International Labour Organization, the World Bank, the World Economic Forum, the European Commission, and Social Watch, gender inequalities persist in labor markets both globally and regionally for all countries of the world and discriminate more against women. These inequalities also prevail in Türkiye.

Kadınların ilerlemesini ulusların gelişmesinin önemli bir stratejik boyutu olarak kabul eden Dünya Ekonomik Forumu (World Economic Forum/WEF), toplumsal cinsiyet eşitliğini göstermek üzere 2005 yılından itibaren Küresel Toplumsal Cinsiyet Uçurumu Raporu’nu yayınlayarak Toplumsal Cinsiyet Uçurumu Endeksi (Gender Gap Index/ GGI) tespit edilmektedir. Bu endeks, kadınlarla erkekler arasındaki eşitsizliğin derinliğini ölçmek için, ekonomik katılım ve fırsatlar; eğitime erişim; sağlık ve hayatta kalabilme; siyasal güçlenme ile birlikte dört kritik alan belirlemektedir. Raporda, ülkelere 0 ile 1 arasında bir puan verilmekte, puan 1’e yaklaştıkça uçurum kapanmakta, 0’a yaklaştıkça derinleşmektedir.

According to the “Gender Equality Report” published by Social Watch in 2023, in the “Gender Equality Index/GEI”, countries are scored and ranked based on three main criteria: “education”, “economic activity” and “women's empowerment”. In the field of education, the GEI considers gender disparities in school enrollment and literacy at all levels. In the field of economic activity, it calculates openness in participation in economic activities, income, and employment. In the field of women's empowerment, it measures disparities in highly skilled jobs, parliamentary representation, and senior management positions. The GEI calculates a value for gender discrimination in all three areas on a scale from 0 to 100 (best level). The GEI is calculated as the arithmetic average of the three domains mentioned above.

In many traditional cultures, women are associated with caregiving roles and often bear greater family responsibilities than men. Gender norms that define appropriate behaviors for men and women are closely linked to familial altruism, which is socially constructed within families. These responsibilities, created within families and reproduced across generations, contribute to shaping women’s “gender” (West and Zimmerman, 1987; Brines, 1994). The gender roles attributed to women's actions create two fundamental problems in terms of women’s labor. The first problem is that, due to these responsibilities, women are often excluded from the workforce and cannot benefit from the economic and social advantages that come with employment. While the responsibility for family income traditionally rests with men, caregiving responsibilities are assigned to women. This leads to caregiving being perceived as women’s primary societal duty, which hinders their participation in the workforce and results in the underemployment of women already in the labor force. The second problem relates to women who are employed. Gender norms not only influence the supply of labor but also shape the structure of professions in which women are employed. Women are predominantly employed in professions involving "care labor." Care labor, which requires personal attention and is performed in a face-to-face, relational context, deviates from traditional economic job definitions. In this context, care labor is not merely about providing services but is also related to the motivations of those who provide it. Care services involve personal interactions between providers and beneficiaries, which create emotional bonds. These emotional connections are historically and culturally imposed on women through norms that define caregiving for others (children, spouses, and the elderly) as their responsibility. The requirements of care labor encourage women to internalize communal and altruistic values, such as working with and for others. Conversely, the social norms resulting from men’s responsibility for family income lead them to internalize more competitive and individualistic values, such as focusing on wages and career advancement. These differing internalization processes further embed gender into job definitions, reproducing the inequalities created within families in the employment process. Consequently, jobs requiring care labor are not financially valued because they are seen as an extension of what women "naturally" do within households, and these jobs are paid less than "real" jobs. As a result, women are horizontally stratified in the service sector at a relational level —a phenomenon also referred to as the “glass wall.” This horizontal stratification concentrates women in lower-paid and insecure sectors compared to men. Since relational jobs resulting from care labor are perceived as women's natural roles, women are not sufficiently rewarded. While such professions may be considered stepping stones for women’s empowerment and enrichment, women often cannot reach managerial positions even in industries where they are said to possess natural advantages. This situation, known as the “glass ceiling,” causes men to achieve vertical stratification in managerial roles, even in sectors where care labor predominates. As a result of these developments, women are concentrated in the service sector and primarily in relational professions due to the nature of care labor. These professions, seen as an extension of the caregiving women already perform in households, are not regarded as deserving of high wages. The fundamental reason behind this is the social undervaluation of care labor. When care labor is undervalued, related professions carried out in relational contexts are also deemed unworthy. Thus, these professions, viewed as extensions of women’s existing roles, are precarious, and the rewards they offer are reduced. Consequently, care labor leads to the concentration of employed women in lower-paid and insecure jobs while also preventing them from reaching managerial positions in these fields, where higher earnings could be possible.

In the workshop on Ecotourism held within the scope of the project, the EcoTourism Action Plan of Ayder Plateau (August 01, 2024 - December 31, 2026) was prepared.

The action plan is in the folder. These pdf files should be downloaded when clicked on.

Two field research were conducted on the ecotourism potential of Kaçkar Mountains National Park and Fırtına Valley and women's labor. You can access these research reports at the following links:

Association of Turkish Travel Agencies (TÜRSAB): www.tursab.org.tr Gender Studies, o.p.s. (Czech Republic): www.genderstudies.cz Italian Association for Responsible Tourism-AITR (Italy): www.aitr.org Rize Governorship: http://www.rize.gov.tr/ Artvin Governorship: http://www.Artvin.gov.tr/ Rizem Culture and Tourism Association: www.rizemturzim.com.tr Markarize Culture and Art Association: https://turkiyeturizmansiklopedisi.com/markarize-kultur-ve-sanat-dernegi Rize-Artvin Tourism Association: web address is not available. Rize Culture and Tourism Directorate: https://rize.ktb.gov.tr/ Kaçkar Mountains National Park Directorate: https://bolge12.tarimorman.gov.tr/Menu/46/Kackar-Daglari-Milli-Park-Mudurlugu Association of Civil Society Development Center: https://www.stgm.org.tr/ Women's Movement Association at the Rural Region (BIZ DE VARIZ): http://www.bizdevarizdernegi.org/ Civil Society Dialogue Program VI Civil Society Dialogue for Strong Women Project, Women in Local Government E-platform: http://www.bizdevarizdernegi.org/e-platform-tr/e-platformtoplanti.html Rize Provincial Directorate of Agriculture and Forestry: https://www.ogm.gov.tr/trabzonobm/kurulusumuz/rize-orman-isletme-mudurlugu Artvin Provincial Directorate of Agriculture and Forestry: https://artvin.tarimorman.gov.tr/

Within the scope of the project, we prepared a 1.4-minute documentary. Please click here to watch our documentary:

You can access the audio and video report of the research on women's labor via this link:

You can access the audio and video report of the research on ecotourism via this link: